NOW Articles Written By Members

An Argument for Collecting Half Dollars

Late Night and a Russian Type Set

Old Country Coins: Newfoundland’s Rarest 5-Cent

Milwaukee Medals: Fifth Ward Constable

A look back at a common, but classic commemorative – Wisconsin’s Territorial Centennial

A side-tracked story: Mardi Gras Doubloons

A look back at a collecting specialty – the O.P.A. ration tokens of WWII

Bullion And Coin Tax Exemption – Act Now!

Is There A Twenty Cent Piece We Can Add To A Collection

Capped Bust Half Dollars: A Numismatic Legacy

U.S. Innovation Dollars: Our Most Under-Collected Coin?

My 2023 ANA Summer Seminar Adventure

>> More articles in the Archive

For more NOW Articles Written By Members,

Numismatics and the L.G. Kaufman Coin Collection

[by Sue Hornbogen]

(This wonderful article comes to us courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center, and its author Sue Hornbogen. The MRHC is a 101 year old historical society that now operates a history center, museum, and research library. I urge all NOW members to make the short trip to the U.P. to view the amazing Kaufman collection located within the downtown Flagstar Bank and visit the Marquette Regional History Center at 145 W. Spring Street, Marquette, MI 49855. 906-226-3571. Marquettehistory.org. – Editor)

Coin collecting has been an interest or hobby for many since coinage was invented by the Lydians around 750 BC. It has been referred to as the hobby of kings since many leaders, Caesar Augustus for example, collected coins from around the world. Coins can be considered the “newspapers of the day” because they depicted what was happening at the time of their making. Images on coins denote military victories, display the faces of past and current kings, queens and emperors, or in the United States, past presidents and people who influenced our country and culture.

How many of us have coin collections started as children and housed in the blue Whitman folders purchased at Ben Franklin or Woolworth’s? How many of us continue to search our pocket change for old coins? How many of us consider(ed) ourselves numismatists? How many of us even know what the term means?

Numismatics is the term that describes the study of coins, medals (coin-like objects), and banknotes, and the collection of these artifacts. Austrian priest, Joseph Hilarius Eckhel, was an important numismatist who developed methodology in the 1790s. In his Doctina Veterum, an eight volume work studying the coins of the Greeks and Romans, Eckhel started a standardized method of studying and cataloguing the coin collections of Europe. Later European universities established numismatic chairs under the supervision of historians and archeologists according to the American Numismatic Society.

However, in America, interest in coin collecting and study developed along with the United States. From the beginning, coins were scarce and barter was the common means of trade. Additionally, there were no ancient coin finds here, and there was no academic tradition until later. In cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, numismatic societies began to appear in the 1850-1860s, but coins as an academic disciple never developed at the university level.

From a historical perspective, coin circulation in early America was intermittent at best. Coins that did circulate were from Europe and they tended to go back there in exchange for European goods. In America, barter was the predominant form of trade and money substitutes included farm produce, rice, tar, and wood. From 1607-1775, powder and shot were valued as well as furs and wampum. Colonial paper money came into use around 1690 in Massachusetts and was used to finance the Revolution. Tobacco notes, another form of paper money based on grades of tobacco, were used beginning in 1727.

Prior to 1800 and up to 1830, most American minted coins never made it into circulation. Ninety-five percent of the silver or gold coins were hidden in bank vaults to back the bank’s paper money. The remaining coins were melted down by manufacturers to make goods or traded on the metal market. Minor currency, small coins of silver worth one to five cents, remained in circulation since they were not considered worth melting down.

The government moved to stabilize the monetary system in the United States as early as 1791 when the First National Bank of the United States was chartered by Congress. The bank would be controlled by the government and its purpose was to advance the economy by providing loans for agriculture and business. In addition, the bank would issue paper money, regulate the state chartered banks, provide a safe place to deposit federal funds, and make tax collection easier.

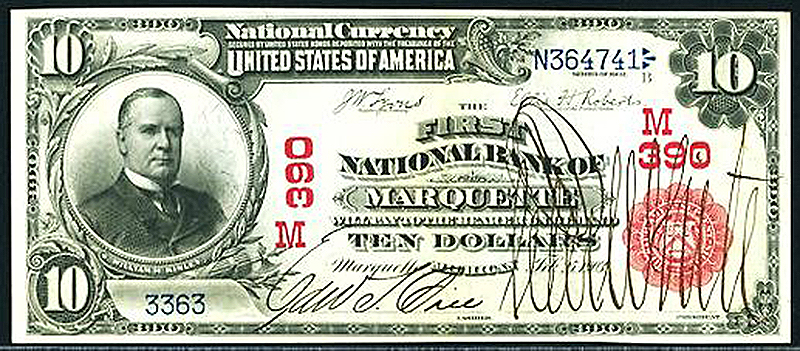

The Marquette County Savings Bank, chartered in 1864, was the 390th chartered bank in the nation. Nathan M. Kaufman was a president of the bank, also served as mayor of Marquette and he was an avid coin collector. In fact, N.M. Kaufman’s coin collection was known to be one of the “largest and most varied collections of United States coins privately held in the world.” The collection included an 1825/4 $5 gold piece which was one of only two known to be in existence. When Nathan died in 1918, the vast coin collection passed down to his younger brother, Louis G. Kaufman. According to the Mining Journal dated November 1, 1927, Louis G. Kaufman opened the First National Bank of Marquette in its newly built home on the corner of Front and Washington Streets. One of the special features of the new magnificent building was a room equipped with vaults to house the coin collection.

Kaufman collection East wall safe

Part of the N.M. Kaufman Coin Collection was sold at auction in the 1970s. The remaining Kaufman Coin Collection is still on display at the bank now known as Flagstar Bank in downtown Marquette and is open for public viewing. The care of the display is a collaboration with the Kaufman Foundation, the Marquette Regional History Center and Flagstar Bank, formerly Wells Fargo Bank. Wells Fargo believed the collection should remain in the community because of its historical significance to the area. The History Center provides field trips to view and learn more about the collection. There are plans to add more interpretation to the collection in the near future. The collection is indeed a “newspaper of the day” with numismatic examples of Confederate currency, fractional currency, Colonial and Continental currency, Civil War tokens, “iron money,” and National Bank notes.

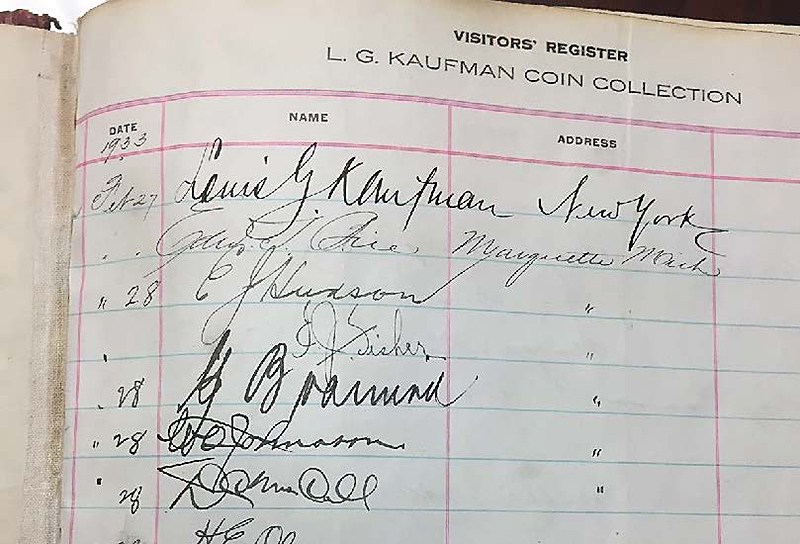

Visiting the collection is fascinating, yet daunting; especially to the novice coin collector, however, the history of the coins contained in the Kaufman Coin Collection are accessible even with no numismatic background or knowledge of numismatic terminology. The collection includes coins and paper money whose purpose and history are explained in the “Highlights of the Louis G. Kaufman Coin Collection” notebook provided by the Kaufman Foundation. On the table with the notebook is the guest ledger began by L.G. Kaufman in 1928.

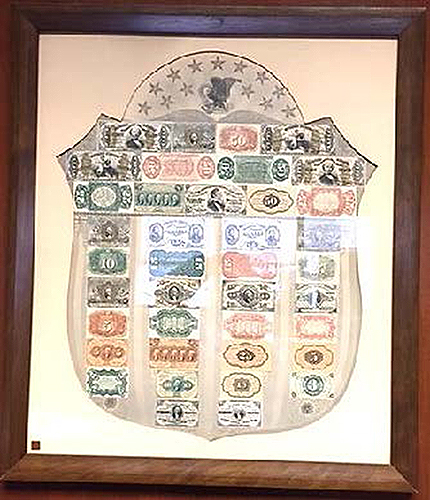

The collection has several examples of fractional currency or “shinplasters” so nicknamed due to their value of less than one dollar. This type of currency was issued by the U.S. government in fractions of a dollar to 5 cents, 10 cents, 25 cents and 50 cents first in the form of postage stamps. This currency kept business going as gold and silver coins disappeared after the Civil War, and once the stamps were printed without postage glue, everyone was happy. In 1863, fractional currency was released in the form of small paper notes with a red or green back and details like a key within the seal that made them harder to counterfeit.

Example of Fractional Currency

The fractional currency shield, issued by the Treasury Department and sold to banks, was used to detect frauds. The shields came in three colors, gray, pink and green. The 39 different fractional notes on the shield were printed on one side only using the actual currency plates. The shields were then framed and hung for easy employee access. The Kaufman shield has a gray background and has been professionally matted and framed.

There are 264 Civil War tokens displayed in the collection. As the government issued coins disappeared for circulation, these one cent tokens were minted by private businesses beginning in 1862. There are three kinds of Civil War tokens - store cards, patriotic tokens and sutler tokens. Store cards display the name and location of the business where they were minted. For example, Lindenmueller store cards were minted and distributed by Gustavus Lindenmueller, a New York City barkeep.

Lindenmueller Civil War Token. Actual size 19mm.

Patriotic token. Actual size 19mm

Many Civil War tokens were minted in the Union States with patriotic slogans and images on them. More commonly known as Patriotic Tokens, slogans used included “Army & Navy”, "Union For Ever" and “Old Glory", while images included the U.S. flag or a cannon.

Sutler token. Actual size 19mm

Like store cards, Sutler tokens displayed the name of the army unit and the name of the sutler, a civilian merchant who was licensed to supply that unit with goods. Generally speaking, these tokens are the rarest.

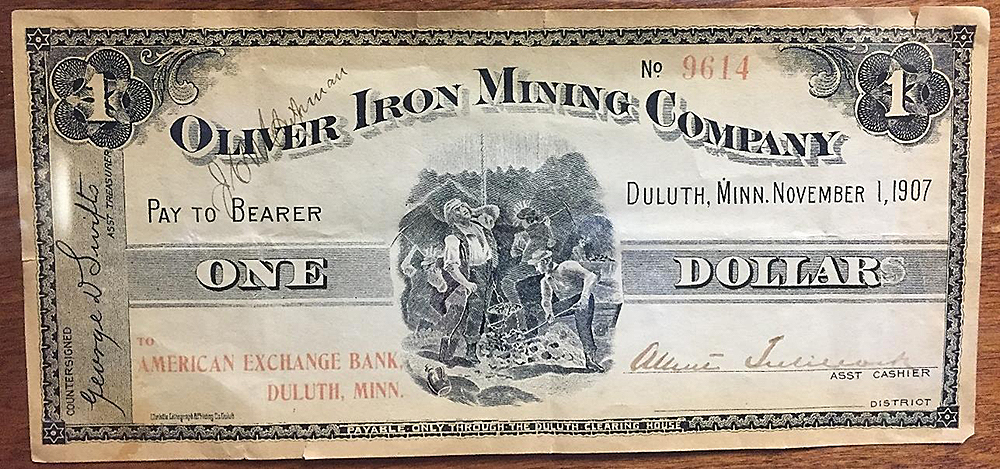

Scarcity of hard money was common throughout the nation. Consequently, there were no cash reserves in the Upper Peninsula, yet there was a booming mining industry with workers who needed to be paid. Mining companies took matters into their own hands and began printing their own money known as script. In the Upper Peninsula, script was known as “iron dollars” according to D.A. Guiliani in his 2001 article for Lake Superior Magazine. Money to back the script was drawn from the company bank fund. As the 1800’s came to a close, the company script was replaced by hard cash as the nation stabilized its monetary system.

Iron Dollar

Bank Note with Peter White signature.

The east safe holds examples of National Bank notes issued by the National Bank of Marquette and its successor, the First National Bank and Trust Company. All the notes are signed by L.G. Kaufman with the exception of the note on the top which is signed by Peter White, president of the bank in 1901. In a recent article printed in the Bank Note Reporter, Peter Whites’ signature was “one of the most flamboyant known to national note collectors.” The article goes on to say that White’s signature tops them all and that the bills he signed were the perfect canvas for his signature. Considering cursive handwriting is no longer being taught in most public schools this certainly may become a lost art.

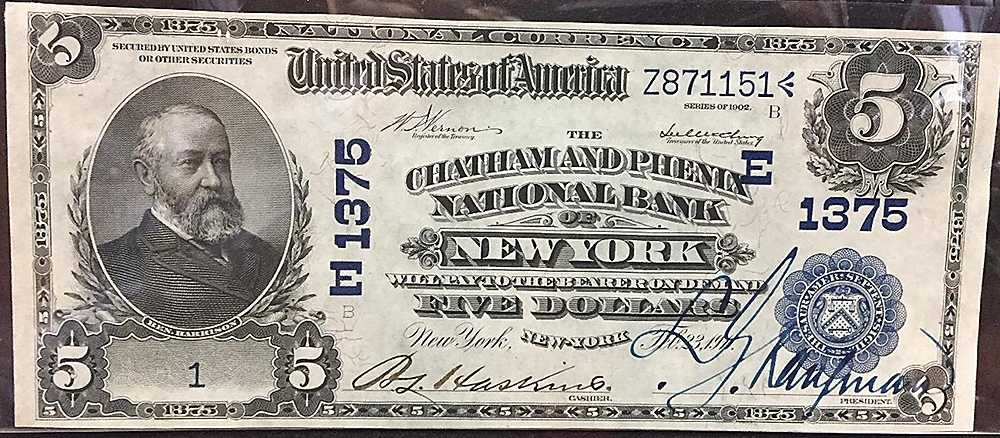

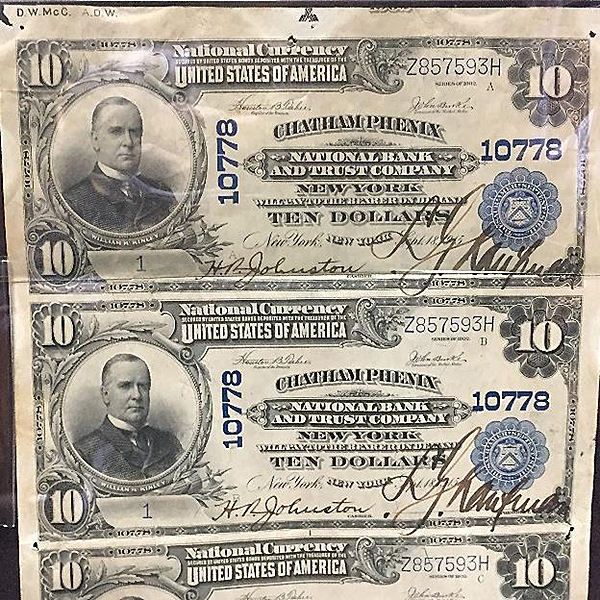

Included in this display are notes from the Chatham and Phenix National Bank and Trust Company because L.G. Kaufman was also president of that bank at the same time, a very unusual occurrence. The Chatham and Phenix notes are interesting for a couple of reasons. One bank note sheet is uncut. Bank notes were printed by the Treasury Department and sent to the bank. Prior to circulation, the notes were signed by the bank cashier and by the bank president and then cut apart which sometimes led to ragged edges.

L.G. Kaufman's signature

Uncut banknotes with

L.G. Kaufman’s signature overprinted

by outside printing contractor.

L.G. Kaufman’s signature fits nicely on most of the notes. However, on the uncut notes the signature is large and overlaps the edges. As the number of bank notes increased, local printing contractors were engaged to overprint the necessary signatures on the notes to save time, and no doubt, a sore hand. This large signature is an example of a local contractor overprinting L. G. Kaufman’s signature on the bank notes.

Bank legislation was amended in 1920 to allow bank signatures to be engraved on the printing plates thus ending the task of hand signing or rubber stamping signatures or paying a local contractor to overprint signatures on all the bank’s new notes.

A breakdown in communication between the Chatham & Phenix Bank and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing involving three orders for new plates with signatures resulted in bank notes arriving with no signatures. To fix the error, the Bureau offered to overprint L.G. Kaufman’s signature on the bank notes between 1926 and 1929. This was the one and only time in history that the Bureau offered to do this for any national bank. However, it cost the Chatham Phenix Bank $2,593.85 and made the notes from this era highly collectable.

Coin collecting continues to be an interest and hobby for many. As a “newspaper of the day,” coin collection lesson plans can be found online to not only teach the value of money, but teach history as well. The L.G. Kaufman Coin Collection is a local treasure for teaching and learning for all ages.

Over the years, the Mining Journal has periodically reminded the public that the L.G. Kaufman Coin Collection is open to the public. Under the curatorship of the Marquette Regional History Center and the open door policy of Flagstar Bank, the collection can be viewed during Flagstar’s business hours Monday through Friday, 9:00 - 4:00 pm. I encourage you to go see this incredible collection of banking history. While you are at it, take time to look at this beautiful historic bank building. It is a real gem right here in downtown Marquette.

Page one of the Visitor's Register began in 1928. First signature, Louis G. Kaufman.

Have an interesting numismatic topic you’d like to share with your fellow NOW members?

Send your article to evan.pretzer@protonmail.com today!!!