NOW Articles Written By Members

An Argument for Collecting Half Dollars

Late Night and a Russian Type Set

Old Country Coins: Newfoundland’s Rarest 5-Cent

Milwaukee Medals: Fifth Ward Constable

A look back at a common, but classic commemorative – Wisconsin’s Territorial Centennial

A side-tracked story: Mardi Gras Doubloons

A look back at a collecting specialty – the O.P.A. ration tokens of WWII

Bullion And Coin Tax Exemption – Act Now!

Is There A Twenty Cent Piece We Can Add To A Collection

Capped Bust Half Dollars: A Numismatic Legacy

U.S. Innovation Dollars: Our Most Under-Collected Coin?

My 2023 ANA Summer Seminar Adventure

>> More articles in the Archive

For more NOW Articles Written By Members,

Troubled Journey

by Jeff Reichenberger #1933

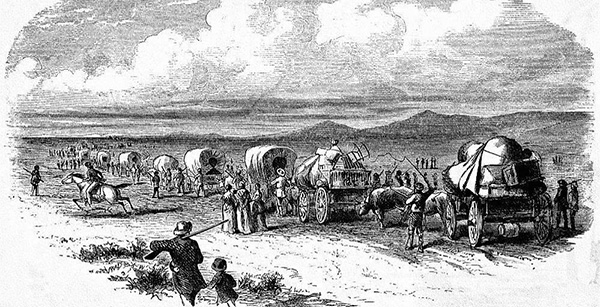

In the late-1830’s, wagon trains heading west became commonplace, and by the end of the 1840’s there was an endless line of wagons from the Midwest to Oregon and California. Of course, the gold rush of 1849 made the end of the decade the most congested western migration in history. But prior to the gold rush, enthusiasm for traveling west was very much alive. Midwest farmers who endured economic hardship through the end of the 1830’s and into the next decade were eager to start fresh in a new land touted by newspapers that promised perfect weather and fertile soil.

Franklin W. Graves was one of these farmers. He, his wife Elizabeth, and their nine children, ages infant to twenty-two, worked their 500-acre farm in Illinois. They had been living in subsistence since the U.S. economic collapse in 1837, unable to sell goods at any profit. But by 1845 an economic upturn brought speculators and land-buyers. So, when Franklin was offered three dollars an acre, he jumped at the chance. The Graves family would pack up and travel west. It was April 1846.

In those days, large bank transactions were conducted with hard money – gold and silver. Paper money had become unreliable. The economy of the United States was driven and backed by foreign minted coinage, along with a smaller percentage produced by the still-growing U. S. Mint.

So, Graves returned from the bank with $1500 in coinage ($50,000 in today’s money) - mostly large denomination foreign silver and U. S. half dollars. He now had to consider transporting the hoard safely across the country, cached within their three covered wagons. This was no easy task, $1500 in coins made up a substantial weight and bulk. Consider that among the stash were U. S. Capped Bust Half Dollars issued from 1807 to 1836. Each of these coins weighed approximately a half ounce. Hypothetically, if the payment consisted entirely of Capped Bust half dollars the hoard would weigh nearly 95 pounds! A stack of 20 Capped Bust half dollars stands approximately an inch and a quarter in height. 3000 of them would equal about 188 linear inches of stacked coins. Fifteen and a half feet!

Graves made two support cleats to run crossways on the bottom of one of the wagons to support a table that was attached to the floorboards above. These cleats were about four feet long, several inches thick and six inches in depth. He drilled rows of holes in the cleats big enough to hold stacks of coins. He then attached the cleats underneath the wagon, concealing the loot.

Slow Going

The family and all their worldly possessions left Illinois on April 12, 1846. The going was slow, spring rains were heavy, and the oxen and wagons bogged down often. They crossed the Missouri River in late May, it was here that most wagons heading west fell in line like marching ants on the Great Platte River Road. This is where many emigrants encountered Native Americans and tall plains grasses for the first time. They made Fort Laramie (near what is now the Nebraska/Wyoming border) in early July. Days beyond Fort Laramie, still following the Great Platte Road, there came to be a fork, where the road gently parted. To the north was the more well-known and proven Oregon trail, to the south the less traveled California trail – said to be faster and cover less mileage.

Feeling time was of the essence (getting over the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range before winter was imperative), Graves chose the south trail hoping to make up lost time. There was another larger party just days ahead of them that he hoped could help guide them through the ever-changing, ever-worsening terrain.

Ten days later the Graves family caught up to the larger group and joined them. Unfortunately, their troubles were only beginning. Call it a simple twist of fate, but the large party Graves had joined was led by a man named George Donner, and as they say, the rest is history.

There is no need to discuss the fate of the Donner party in this article, the tragedy has been studied and retold countless times. But let us continue to focus on the Graves family with a numismatic eye.

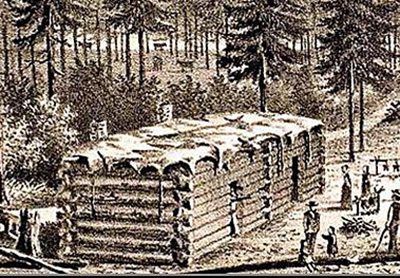

As they struggled in the mountains and winter weather set in it became a forgone conclusion that they would have to winter in the mountains. The emigrants constructed shelters. The Graves shared a ‘double-cabin’ with another family near the eastern end of Truckee Lake (later to be renamed Donner Lake), it was early November 1846.

Franklin Graves did not give up making attempts at crossing the summit pass despite the outrageous snowfall, now ten feet deep. One time he and two others set out on foot only to be beaten back by a combination of weather, terrain, and physical exhaustion. Another time in mid-December, Graves fashioned sets of snowshoes out of oxbows and hide strips. They were cumbersome but serviceable and fifteen people made the trek, including Franklin and his two eldest daughters. They made the summit, but the weather worsened. They were stranded near the pass, freezing and exposed. Franklin Graves died late on Christmas Eve with his two daughters at his side. The girls, along with five others would ultimately survive, reaching a California ranch in late January 1847. Franklin and seven other snowshoers perished on the mountains.

Elizabeth’s Burden

Back at the lake cabin, Mrs. Graves had the task of keeping the rest of the family alive with nothing to eat but boiled ox hides. She still did not know the fate of Franklin or her daughters. In the first week of March a relief team descended onto the camps at Truckee Lake with meager provisions and a short window of good weather to try to take the malnourished families out of the mountains. The younger children had to be carried out. Elizabeth had the extra challenge of preserving her family’s money. These coins would be the foundation on which the family would start life in the new land.

One of the men helped her retrieve the coins from the wagon cleats that were buried in snow, however, she was not familiar with these men and overheard several of them joking about who would divvy up the Graves money. She resolved to carry the heavy coins herself, along with her one-year-old daughter. The first day the group made only two miles, not halfway past the lake. The next day, March 4, Mrs. Graves, realizing she could not carry the burden of the coins, lagged behind the others, she found a patch of earth that had come through the melt, dug a hole, and buried the coins. Then gathered her infant and followed the others.

Again, a snowstorm raged. The party was stranded for three days just two miles from the summit. When the storm finally broke, it had taken more lives, including Mrs. Graves. With her death, the location of the Graves family treasure was lost.

In all, six Graves children survived past 1847: Sarah (22), and Mary (20), William (18), Eleanor (15), Lavina (13), and Nancy (9). Jonathon (7), and Elizabeth (1) died shortly after being rescued. Franklin, Jr. (5), along with his parents, Franklin Graves (57), and Elizabeth Graves (47) died in the mountains.

Found!

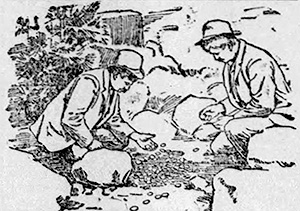

Illustration of Reynolds and friend inspecting

the treasure created from a photograph

by the San Francisco Examiner newspaper,

May 24, 1891.

May 14, 1891 – some 45 years after the ordeal, a mineral prospector named Edward Reynolds was digging around the north side of Donner Lake when he spotted a coin poking through the dirt. Scraping the surface, he unearthed a dozen more coins. Thinking he was onto a buried treasure; he covered the site and went back to town and solicited the help of a friend. The two returned and before nightfall had dug up nearly 200 coins. The next day they returned with the aid of Charles F. McGlashan, who had become an authority on the Donner party. He conducted many interviews with survivors as the owner/editor of the Truckee Republican newspaper at the time and wrote a book about it; The History of the Donner Party: A Tragedy of the Sierra.

Inventory was taken and found there to be no coinage dated after 1844, that, coupled with the makeup of the hoard, and McGlashan’s firsthand interview accounts with the Graves and other families, assured there could be no doubt that this was the Graves family money, buried there by Mrs. Graves on March 4, 1847.

Accounts suggest the money was subsequently divided between the Graves family and the finders, the percentages unknown.

In 1993, the Graves family descendants held a reunion at a public site near the California ranch where their ancestors gathered after the ordeal nearly 150 years earlier. Some of them have coins that were passed down to them through generations. They talked fondly about their pioneer ancestors and treasure the coins to this day.

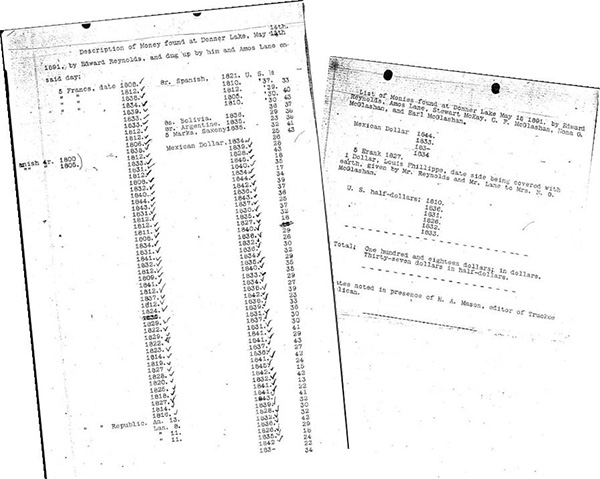

Original inventory taken on May 15, 1891, witnessed by Edward Reynolds, Amos Lane, Stewart Mackay, C.F. McGlashan, Mona McGlashan, Earl McGlashan, and H.A. Mason, who was the current editor of the Truckee newspaper at the time.

Coinage

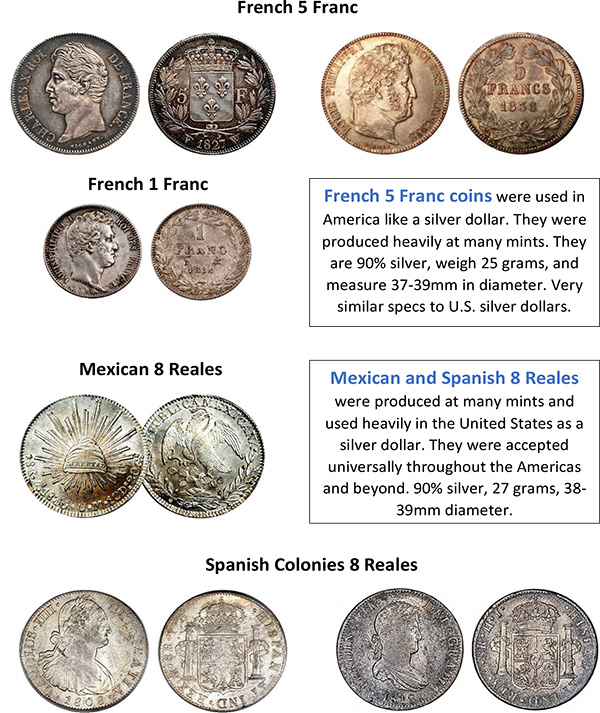

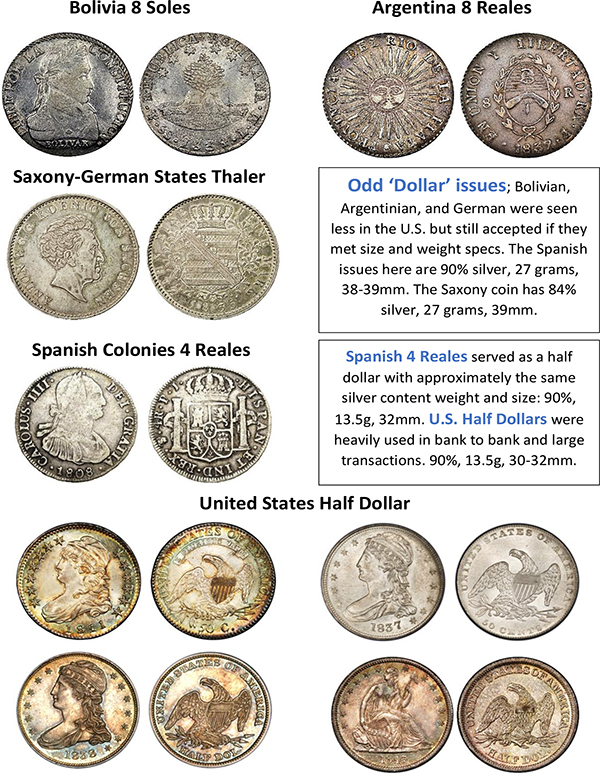

The Graves hoard reflects the economics of America at the time – a mixed bag of silver coinage mostly originating from Spain and France along with a smaller percentage from other countries, including the United States – this system continued until the Act of February 21, 1857, which ended the legal tender status of foreign specie in the U.S.

A look at the original type-written inventory sheet shows a total of 192 coins - 118 dollar-equivalent coins and 74 half dollar coins. The ‘dollar-size’ coins consist of 56 Five Franc pieces, 53 Mexican 8-Reales, 7 Spanish Colonies 8-Reales, 1 Thaler from Saxony of the German States, and 1 One Franc Piece erroneously described as a dollar-equivalent size coin. The ‘half dollar-size’ coins consist of 2 Spanish Colonies 4 Reales, and 72 United States half dollars.

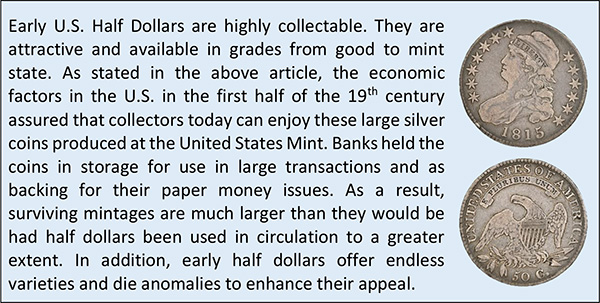

It is no surprise that there are a lot of U.S. half dollars represented in the hoard. Capped Bust Half Dollars (1807-1836) were minted in abundance compared to all other denominations being produced by the U.S. Mint during that time. Paper money was untrustworthy, and the Half Dollar was the largest silver coin minted in quantity, which banks preferred for substantial transactions. Thus, they became the workhorse for the U.S. economy, alongside qualified legal tender foreign coinage.

COIN TYPES REPRESENTED IN THE GRAVES HOARD

Sources for ‘Troubled Journey’:

Brown, Daniel James. The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of a Donner Party Bride. New York: HarperCollins 2009

Ellsworth, Spencer. Records of the Olden Time: Or Fifty Years on the Prairies. Lacon, IL: Home Journal Steam Printing Establishment. Reprint, Henry, IL: M&D Printing, 1992.

McGlashan, Charles F. History of the Donner Party: A Tragedy of the Sierra. Sanford, CA: Sanford University Press, 1947 (reprint of the revised edition of 1880)

Schilke, Oscar G.; Solomon, Raphael E. America’s Foreign Coins: Foreign Coins with Legal Tender Status in the United States 1793-1857. New York: The Coin and Currency Institute, Inc. 1964

Schmidt, Tracy L., Michael, Thomas. Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801-1900. Stevens Point, WI. KP-F&W 2019

Souders, Edgar E. Bust Half Fever: 1807-1836. Rock River, OH: Money Tree Press, 1995

Stewart, George R. Ordeal by Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963

"Graves Coin List”, Charles Fayette McGlashan papers, BANC MSS C-B 570, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Folders 104-105

“Half a Century Buried, the Lost Treasure of the Donner Party Found at Last, Relics of a Historic Tragedy.” San Francisco Examiner, May 24, 1891. P. 13, c. 3-5. No author cited.

Have an interesting numismatic topic you’d like to share with your fellow NOW members?

Send your article to evan.pretzer@protonmail.com today!!!