NOW Articles Written By Members

An Argument for Collecting Half Dollars

Late Night and a Russian Type Set

Old Country Coins: Newfoundland’s Rarest 5-Cent

Milwaukee Medals: Fifth Ward Constable

A look back at a common, but classic commemorative – Wisconsin’s Territorial Centennial

A side-tracked story: Mardi Gras Doubloons

A look back at a collecting specialty – the O.P.A. ration tokens of WWII

Bullion And Coin Tax Exemption – Act Now!

Is There A Twenty Cent Piece We Can Add To A Collection

Capped Bust Half Dollars: A Numismatic Legacy

U.S. Innovation Dollars: Our Most Under-Collected Coin?

My 2023 ANA Summer Seminar Adventure

>> More articles in the Archive

For more NOW Articles Written By Members,

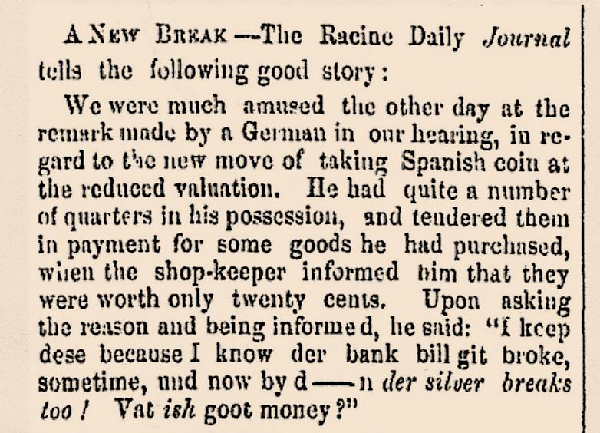

What Was ‘Goot’ Money in 1857?

By Dave Herrewig #2382

It might be easy to find historic newspaper articles online, but understanding what they are talking about is the more interesting part. What was going through people’s minds back then? That’s what I’m attempting to answer here.

A friend who knows that I like historical references to coins sent me the “A New Break” download above. It came from the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel of February 11, 1857 which picked it up from the Racine Daily Journal. (Today, it’s in the Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers database.) The year 1857 was an important time in American coinage history: The Coinage Act of 1857 was about to go into effect and demonetize foreign coins that had been legal tender in the United States for decades. And, this former legal tender was not going to be redeemed at its traditional value.

The German immigrant’s complaint shows how these events affected people at the time. Many Americans were using old, worn silver coins; these often came from Spain’s possessions in the New World, and from the countries that grew out of the Spanish colonies. A silver Spanish two real “quarter” or a silver Mexican two real piece (which was not officially legal tender but was commonly accepted) would have passed for 25 cents before the Act was passed.

It seems clear that the shop owner in this story knew that such coins would soon be redeemed by the Federal Government for only twenty cents under the new act, so he offered that amount to the immigrant. Likewise, one real would bring only 10 cents (instead of the usual 12-1/2) and the half real would bring 5 cents (instead of the usual 6-1/4).

The statement that “…bank bill git broke…” can refer to many unfortunate stories of early banking in Wisconsin. “Broke banks” were those which had failed, and could not redeem their paper notes for the value of the note. In this time before Federal regulation, even if banks didn’t fail their currency was often discounted at less than the value of their notes. Often these banks were located outside of Wisconsin but their currency circulated in the state, as a means of exchange was sorely needed on the frontier. There was no regular United States paper money then.

There were well-publicized failures of banks and dishonest practices by bank owners during the Wisconsin territorial era. Once Wisconsin became a state in 1848, voters didn’t approve of any banks being organized in the state until 1852. Though it hadn’t happened by the time of this story, more banks across the country failed later in the year during the Panic of 1857.

So, the frustration of the German immigrant was understandable. Silver money of foreign origin, which had been used in the United States for decades, was about to be declared no longer valid at its old face value. And, commonly used bank notes were notoriously unreliable. My guess is that even though the newspaper editors were amused by this incident, they understood what the man was talking about.

There is a footnote to this story: The Coinage Act of 1857 made another big change to U.S. currency; it ended the large copper cents and half cents. To replace them, a smaller copper-nickel cent was introduced with the Flying Eagle design. Once the process of surrendering foreign coins began, there was a clause that would have permitted the immigrant to receive twenty-five cents for his quarters IF he could have gone to the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. There, the Mint accepted old Spanish coins (and Mexican coins) that were less than a dollar and paid twenty-five cents for a two real piece. They paid traditional value for the real and half real, and paid these money changers with Flying Eagle cents. This was an effort to popularize the new coins. We’ll never know if the German immigrant knew that option.

Left to Right: Spanish 2 reales, 1 real, ½ real, Mexican 2 reales.

Have an interesting numismatic topic you’d like to share with your fellow NOW members?

Send your article to evan.pretzer@protonmail.com today!!!